It can take a while for the beginner sax player to get to the palm keys and low C-sharp, B, and B-flat fingerings. But when they do, it’s often required scales in band that get them there. Here is how I introduce scales to my private students—in a logical order regarding key signatures and range.

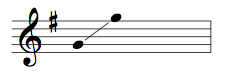

It makes sense to start with G major, since it’s the key most band methods introduce first. The range also sits right in the middle of the horn with the notes the student learns first.

Next up is the C scale one octave, but I see no problem with two octaves as long as the instrument is in good repair. If breath support or embouchure is an issue, we address that and I have the student slur down to low C. They start from low C whenever they are ready.

Only after teaching the F major scale do I get a little picky about the order students practice in. I ask them to practice either F, C, then G major, or the reverse (without explaining much about the circle of fifths).

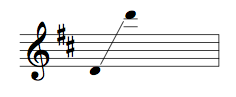

When It’s time for D major, it’s possible two new fingerings are introduced—high C-sharp and high D. Since C-sharp is the same in the lower register but with the octave key, D is the real novel fingering here.

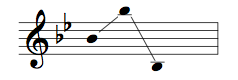

A major doesn’t extend the range, but it does keep going in the circle of fifths. Here my students either practice A, D, G, C, and F major, or reverse the order. After this, we usually come back to flats with B-flat major. The same basic idea applies here as does C major. If the student is ready and has an instrument with no leaks, they can descend two octaves, then start on low B-flat as they are ready. It doesn’t bother me that low B-natural may be skipped.

Next up is E-flat major, which extends the range by a half step ascending. This puts the student at knowing up to three sharps and three flats, still practicing in the order of the circle of fifths.

E major two octaves extends the range up another half step, almost as far as the young player will go!

The first scale with a low B natural is B major.

Finally, F major two octaves, bringing the student to the top note in their fingering chart!

A-flat, D-flat, and G-flat/F-sharp major would be next, after the student can play the entire range.

A few extra thoughts about scales:

I want my students to understand and be comfortable in all the keys, so I have them play tunes, plus improvise and compose simple melodies in each scale they are working on. We often return to a previous melody but in the new key signature. There is no need for the young player to rush through the scales, and even with private lessons it may take four years to get all 12 major scales in.

Circle of 5ths/scale order: I want the student to first understand that C and F have six notes in common, as do G and C major. But F and G only have 5 notes in common, which is why I am particular about the order they practice them in. Then, we talk about the order of the sharps and flats, the patterns involved, and the circle of 5ths by literally writing the key signatures down in a circle.

In the area where I teach, the most common scale audition requirements are similar to the North Carolina all district scales, so I start with those. The ultimate goal is for the student to be able to play any scale in any order in any range with any rhythm, but it seems to me that this is a good starting point.

“Nature is pleased with simplicity. And nature is no dummy”

― Isaac Newton [1]

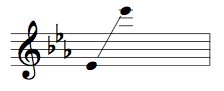

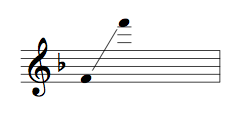

Lately, I’ve been trying out a four-note scale when practicing improvisation. The scale I’ve been using is here:

Even though I haven’t made it a natural part of my improv yet (with maybe one exception), I’ve found it very useful. The above four notes can be used over the following chords: Csus, D minor, E7 (sharp 9, sharp 5), F Major, F7, Gsus7, B-flat Major 7, B-flat 7, and probably various others. (My favorite place to use it would be over a sharp 9, sharp 5 chord.)

But enough typing about it. Here are some early results from the experiments I posted to Vine the other week.

—————–

[1] It seems the quote should be “Nature is pleased with simplicity, and affects not the pomp of superfluous causes."

Recently, I sat down for an interview with local Charlotte sax hero, woodwind doubler, and all around good guy, Tim Gordon. Tim has a new website and recording out.

Below is a slightly edited transcription of our conversation. We started out talking about music education, and preparing to be a performing musician.

—-

Tim Gordon: When I got out of college, I was not prepared at all to be a professional saxophone player. I mean, I thougt I was. But, you know, you’re in college. It’s sort of like being in the third world—it’s not reality, you’re in college. Even if you’re working, you’re in college. You’ve got to say to them, “Oh, I’ve got class tomorrow.”

And then you’re out of college. It felt like the whole bottom fell out, and now what do I do? So, you immediately go out and try to start working, but good luck finding music work right away. I certainly couldn’t do it, moving back to Charlotte. I started doing a day gig after about a month or so, and then started realizing my education had fallen far short of what I really needed to compete with the professional players and be in that group of people.

Mark Catoe: So you must have some ideas about how music education…

TG: Can change.

MC: Yeah. I was talking with someone I went to school with, and they suggested adding music production, writing, and similar things to degree requirements.

TG: I think the idea of offering a commercial music degree, or at least those skill sets. And I may have a tainted view point, but I taught in colleges for combined 30 years. To have a band-based educational system is almost ridiculous, there’s no band after college. And the whole program is set up for band and to train another generation of band directors. The most important people in the school are the band directors. And it’s that way in high school, it’s that way in college. And the whole system just kind of feeds itself, but it doesn’t serve the needs of the professional community. It is extremely important to learn to play in band, be under the direction of a good conductor and participate in an ensemble. But in addition to that we might try to find ways that education can serve the needs of the musical community as well. Plus the arts can’t grow and thrive if there not directed.

MC: They’re not directed?

TG: Towards a goal, a means to an end. You play in band, so what do you do? You really don’t know how to go out and play a gig. You play in band. Someone leads you through it… most band people don’t learn to count. They really don’t learn to play their instrument in tune. They may learn how to tune up to each other while they’re playing along, but they don’t know how to play their instrument in tune.

MC: It’s true.

TG: And so, many of those things really bug me a lot. When I do teach, no matter what age it is, I try to have it based on end results. “How do you think it sounds?” You take responsibility for deciding, “does that sound good, or does it not sound good?” One tool I use a lot now, I record my students. And the first time, they hate it. Because when they first hear it, they go, “Oh… Eww.” The same reaction I had when I first heard what I sounded like. “I didn’t know it sounded like that when I did that thing I do.” After that first initial shock, it usually gets better and better. Somebody can tell you something over and over again, but if you decide that for yourself, you got a better shot at it.

MC: It’s like you’re saying, the current way high school and college music education is set up, is to teach the students to do something that they’ll never have an opportunity to do.

TG: A lot of it is.

MC: In the sense that it’s band based, and when are they going to play in a large ensemble again?

TG: It’s band based, and it’s classical music oriented. And even if you go out and make money making music, how much classical music do you go out and play? This whole idea of studying music history… Music history is important, just like history is important. But to base your whole education on learning classical theory and what Mozart did, and all those dates, at what point do we decide that is not serving our needs anymore? It’s tough to make breaks from the past, it really is. Some of that stuff is necessary and good, but some of it is just the way we’ve always done it. “Well, that’s just the way we do it.”

MC: The Berkley School of Music’s had sucess doing what you’re talking about.

TG: I think they have had sucess. And what makes places like Berkley or Miami or North Texas successful is that they have a team of forward thinking people that can agree on a curricullum and can put it into practice. You have to have extremely qualified people to do things like that. But you don’t have to rewrite the book at every school, you just have to have a good example and be willing to move forward. All those places seem to have—like Dan Haerle down at North Texas—they have a theory guy who has an idea that’s not based in the 16th century, but is very practical, it works, his ideas are solid and concise, and they don’t disagree with traditional harmony, but they present it in such a way that it might be useful. I think it’s not black or white. It’s not like you could just do away with everything. But not moving forward, I see as a big problem.

MC: When you first left school and started a career in music, what are some of the things, like playing commercial music—that’s not something that was in your training, I guess.

TG: Well, I was real fortunate because when I was a kid, there were saxophones and horns in all the bands. I cut my teeth, I had an electric pickup on my sax and I was playing along with Led Zeppelin records when I was in the 9th grade. And I was never snobbish about that stuff. I mean, that music meant something to me, because it was part of my life.

So, as far as all that stuff goes, I never minded making any commercial music. And I had played in bands all through, even college. When I left East Carolina University, and I moved to Winston-Salem, within the first two months of being there, someone called the School of the Arts looking for a saxophone player for a band. And I got in that band, and for three years while I was there I worked every weekend, at least two nights. We’d do a one week job a month. Not only was I making money, but I was playing all the music that was on the radio. So I learned to play with bands at a young age. And I never was snobbish about going out and playing commercial music.

But once I got out of college and I started doing that for a living, I began to realize that, I’m 24, but all these guys out here doing this are all 45. And it’s not snobbery or anything, but it was guys that didn’t necessarily read music, and I have played with some pretty good players, and it wasn’t like they were guys than never made mistakes, you know. (It’s not to shun anybody that hasn’t developed their skills to a certain level. You’ve gotta have time to do that. And that’s a thing that I devoted myself too, and I had help from my peers, my parents, to devote the time into being a better player.) But I could see that, man that was going to get me nowhere in the long run. And I was fortunate to be just good enough to be able to hang around the older guys that were thought of as the really good players. At that time Phil Thompson was a really young guy, but he had all the skills: He was a great reader, he played flute, clarinet, and saxophone, he improvised well. So he was a guy that was getting calls to do the circus and whatever reading gigs there were, big band gigs. The very first big band gig I ever went on, I’m sure I did a terrible job. But then I knew after that. I knew I’ve got to do this to get hired. So I started working pretty hard at being a better sight reader.

You know, when you’re young and dumb, you misinterpret what your job is when you’re standing in front of people playing. This wasn’t about me and my ego. This was about, can you play music that somebody’s gonna want to sit there and listen to for two hours while they have dinner and drinks. So, backing off just a little bit and not playing so loud, it ain’t just about me! But, you know, you have to either learn these things or it doesn’t occur to you.

MC: And some people still don’t.

TG: Well, some people don’t learn those subtle things that it seems like everybody else knows but them. So, I try to be sensitive to, not only the people I’m playing with, but the people that are listening.

Nobody wants to play a jazz gig and have somebody come up and say, “Y’all know any beach music?” Just kill me now. Still, you gotta realize, that where most people are coming from when they listen to music, it’s an enjoyment thing. They just want to pat their foot and enjoy the music. And if they have a favorite song, it’s okay if you don’t play that song, but don’t make snickety remarks about them after they walk away from the bandstand. Realize that they have their own wants, needs, goals.

MC: And really, they’re the reason you’re there.

TG: They’re the reason you’re there. That’s a big point right there. Why do you think someone’s going to hire you? What makes you think that someone should hire you to go play a gig? From the bandstand standpoint, from the sideman standpoint. I’ve been a sideman my whole life, and I have been a good sub, I’ve worked as a sub for saxophone players from all different genres. Because I would never try to steal anybody’s gig. To me, that’s the worst thing you could ever possibly do. And I’ve had good saxophone players do that to me. It happens, and that’s something I would never do. Respect other people: the people that are listening, the other musicians—it’s a small world in that way. You’ve got to do your best to fit in without being overbearing. It’s real easy to be overbearing. Nobody likes that.

MC: Part of being a professional.

TG: Part of being a professional is how you respect other people and musicians. Be respectful. If that’s somebody’s gig, man, that’s their gig. I love getting to play with other saxophone players. I’ve always felt that Ziad and Tony Hayes, those are guys that grew up here in Charlotte, and they’re still playing. I figure if Ziad’s working a lot, I’m going to be working a lot. If nobody’s working, nobody’s working. I’m not in competition with him—I’d like to stand there beside him and play. It’s not a competition.

Yeah, we all need to make money, but it’s a big world out there. He’s got things he’s better at, I’ve got things I might be a little better at. We just fit in where we fit in. In big cities, people realize that, and guys get known for doing a certain thing. Somewhere like here, you can sort of be a jack-of-all-trades. That in itself is okay—I’ve had to do that to keep working more, but you’ve got to realize what you’re better at, and what you’re not. You ought to leave people alone and let them do their thing. There’s lots of great players out there.

MC: Speaking of working, if a player’s getting work, I guess it was 2008 when the Great Recession hit, and things went downhill for a lot of people. Do you find that it’s improved since then?

TG: You know that was the most recent one. I was here in the late ‘80s when we had a recession. And also in the mid-’70s. I was just a kid then, but I remember gas lines and this, that, and the other. And guys a lot older than me were talking about how there was no work. Man back in the ‘80s there were dance clubs that had live music. There were a lot of them around.

MC: Around here?

TG: Around here. There were gigs where you could go out and hear live music and dance, and the bands all had horn players, and guys were out playing, and there were three or four working jazz groups, like Ziad had a group, Tony had a group. Those guys were playing all over the place. They had house gigs here in town. And they played five, six nights a week. You could go out and hear jazz just about any night of the week. They had a gig downtown at the Raddison for a long time. There was a place called Good Time Charlie’s. Both of those bands were house bands at that place for different periods of time. There was just a lot of music going on. This was before Charlotte became a big city.

MC: Wow.

TG: When Charlotte started becoming a big city, all that stuff was closing down. Part of it was because of the, I guess there has to be more attention paid to drinking and driving, and things like that. There just weren’t as many cars on the road. But I guess the economy did play an important part in the decline of the ‘working’ musician.

MC: It does seem like the opposite should happen. If there’s more people, there should be more venues.

TG: It does seem that way, but it hasn’t worked that way.

MC: And this was before people were talking about the decline of the music industry with MP3s and all that.

TG: Oh yeah. Way before that. In the early ‘90s I started traveling a lot. I went out with the Basie Band for a short time. An eye opening experience. Before that time, in the ‘80s, I had it made. I played in a group called The Faction; and a group called the Montuno Jazz Orchestra, which was Jim Brock’s latin band; and I played in a beach band called The Poor Souls. And The Poor Souls were extremely popular among the shaggers. So at the time I was playing with all three of those bands. I was working seven nights a week. But there came a time when all that stuff started shutting down, and it was toward the end of the ‘80s, as the country started going into a recession. So it all started tightening down. And I decided to go back to school, and try again to teach.

But I started traveling with The Four Tops, so I was gone for at least ten years, every weekend and all summer, playing with The Four Tops and the Temptations. I didn’t have to worry about making a living just in town. At that time I also had a gig—part of this is being in the right place at the right time. in 1981, there was a guy named Derek Slep. Well Derek was a guitar player. He had been to Nashville and studied a little bit, and he realized that he was never really going to make a name for himself as a guitar player. He went to Nashville of all places. Derek started a company called Sound Choice. It just so happened, I played on the very first one he ever made. And I guess I must have done okay, because he started calling me. And I had to play through, transcribing and recording all the pop tunes that ever had sax in them. Broadway shows, big band, Billy Joel, anything that had sax. So when I was home from those trips out of town, I had work. And it was good work, it was recording work. Now it didn’t pay a lot, but it was a lot of work, so I learned to be a better sax player. And that’s where I started really playing flute and clarinet. I figured, if I play clarinet, I could do the background; this thing’s got clarinets on it.

MC: That’s not where you started doubling?

TG: That’s where I started doubling. And then, years later, Phil Thompson asked me to sub on a gig for him. I was nowhere near ready to do that gig. I said, “Man, I can’t do that.” He said, “Will you do it? I need to be gone.” I said, “I’ll do it, Phil, but I don’t feel good about it.” And I went, and it was bad, okay? But at the end of those four days, I knew exactly what I needed to do if I was going to be back there ever again. So, then is when I really started working—well, I also started playing flute in the montuno band. But it’s different playing a flute solo than it is trying to play some pretty melody in a broadway show. It was bad enough through the ‘90s, but like I said, I was traveling. But after 9/11, that work just completely shut down. We were going to Vegas four or five times a year, for two weeks at the time, and then it really tightened down. And when this last recession happened, it went really down. I mean, this is a cyclical thing, but it’s never been close to what it was in the ‘80s. And guys tell me it happened in the ‘60s, and it happened in the ‘50s. And each time the music scene has come back, it has come back less.

MC: So it’s like the music scene is not as resilient, or not as prone to come back as other industries.

TG: Well, during the ‘80s, when I was really getting my start as a musician, guys would complain, “These gigs paid the same thing 20 years ago.” And I’m sure you’ve heard guys say the same sort of thing now. It won’t go up.

MC: This does not seem like good news for young musicians!

TG: Here again, what we have to learn to do as musicians, and I’ve done this three times, and I’m in the process of doing it again—you have to reinvent yourself, and you have to move forward. You have to adapt and change if you want to be vital. You’ve got to be forward thinking. You’re smart enough to be involed in social media. It’s something that we all need to take part in, or we’re going to be dinosaurs.

You’re not going to make a living doing what Charlie Parker did. Just forget it. What can you do, what do you bring to the table, how can you figure out how to do this? Do you want to have a wife and kids? Two kids, or you want four? Do you want a car? A house? Some people don’t want those things, and that’s fine. But if you want those things, you’re going to have to really—unless you’re just lucky—you’re going to have to put some thought into it and figure out a way to make things happen.

You’ve got to have a need. I think basically, people are kind of lazy. If you have that college teaching gig, you might be a great player, and you still might love to practice and perform and do all those kinds of things, but you really don’t need to go out and hunt stuff down. But if you don’t have that, you have a need. And you’re going to find a way to do that. I’m in the process of doing it right now, meeting the younger guys, renewing my contacts, figure out what’s going on. I’m not trying to cut in on their action, I just want to understand what is enabling them to be prosperous in the business right now. There are young guys out there doing it, but they’re not at home twiddling their thumbs, they’re out there being involved. If you have enough need, you’ll find a way to do this.

Saxophonist Ted Nash (you may recognize him from the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra) has recently launched “Project: Pro Student Horn.” Here is a short Q&A where he explains a some details about his program to put affordable professional level horns into students’ hands.

______________________

Where did the idea come from to provide more affordable pro-level horns to students?

Ted Nash: Someone brought a vintage alto to me once and asked me what I thought. After playing it I thought I could do a gig on this. I found one at auction and it, in fact, became my main horn for a while (I recorded “The Creep” with it). I didn’t pay much for it, and even with repairs it was a tenth of the cost of a Selmer Mark VI. I bought a few more, different models, and loved playing each of them. I then though this would be a great way to get great-playing horns in the hands of young students who can’t afford (or their parents can’t afford) to invest several thousand dollars in an instrument. That’s when I decided to form this program.

Are there any restrictions on who can buy? (Is it limited to students or those in need?)

To qualify you need to either be pre-teen or not able to afford an instrument. I understand that very young students’ parents are reluctant to spend a lot of money on a horn, not knowing how committed the kid will be. I think making this available to very young kids will help inspire them to continue playing. If a parent or teacher can show (by writing a letter to me) their kid or student really can’t afford a sax then they will (upon my acceptance) qualify. I have had offers from people to help sponsor the program which will help my lower the cost or provide free of charge an instrument to a student who has no means at all to buy one.

You’ve made available ten saxes this year. Is this something that you might continue in coming years?

I have started with ten because that is how many I have now, I can’t afford to do more until I sell some (or receive sponsorship). As this happens I will be able to do more. I expect I will offer more than ten the first year. I will also add tenor saxes at some point.

______________________

For more info, or to contact Ted about participating in the program, visit here.

In the most common band method books, there is this general approach to getting clarinet players to cross the break:

- Play notes up to A in the staff, working down to low F and E below the staff.

- Add the register key to these low notes, maybe playing a few melodies that stay above the break.

- Play melodies requiring the change from A in the middle of the staff, up a second, to B across the break.

It seems to me that, if we want to make crossing the break as easy as possible for beginners, then there are a few important things missing.

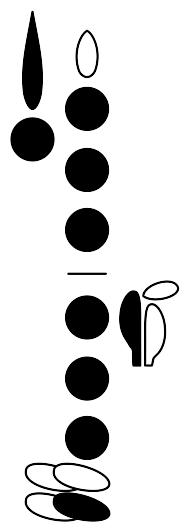

First of all, playing from the A in the staff up a 2nd to B requires this change in fingering:

That’s a lot of fingers to move. At exactly the same time. What has prepared the student for this? Essentially nothing. Before this, they’ve probably only moved one to maybe four fingers at a time. The largest interval in their repertoire is likely a 5th or a 6th.

So what can be done to better prepare students, and give them more success crossing the break? Here’s what I do.

Make sure students use good breath support.

After learning the first few notes, I turn a student’s mouthpiece around and have them play while I finger the notes on clarinet. I then cover a broad range on the clarinet, including notes with the register key. This is important, because the higher notes won’t sound without proper breath support. We talk about voicing as well.

Get students used to larger descending intervals.

Incorporating melodies that have larger descending intervals is the most obvious way to prepare students to cross the break. “Sur le pont d'Avignon” has two descending 5ths.

The slurs are intentional, because they can expose when fingers aren’t moving precisely. If the student can play this cleanly, then they are well on their way to being able to cross the break.

“Over There” starts with a descending 6th. Starting on A, it can be an especially good preparation, since the left hand pointer finger needs to move from the A key to cover the hole for E.

Practicing descending octaves and larger intervals is the next step.

Making sure students can add the register key without uncovering the left thumb hole or moving the other fingers excessively.

The thumb should move only enough to press the register key, and the index finger should not move, really at all. Sometimes students can move the pointer finger so much that they accidentally press the A-flat key.

Playing modified melodies that cross the break.

My favorite starting point for playing across the break is “The More We Get Together,” but modified, so the first note is down an octave.

There are at least two reasons students should be able to play this with success. First, the phrases start on low F, so they don’t need any fingering acrobatics crossing the break—a great starting place, I think. Secondly, crossing the break the other way, in this case from C to B-flat, is much easier.

After this piece, I then proceed to other melodies using decreasing intervals, such as Wagner’s Bridal Chorus.

Again, the slurs are there to ensure clean finger movement.

After working through 10ths (Dvorak’s “Going Home”), octaves (“Happy Birthday to You”), and 7ths (Star Wars theme), 5ths (“My Favorite Things”/“Camptown Races”/“Goodnight Ladies”) they are pretty adept at crossing the break, and can approach playing scales or other melodies with smaller intervals. [1]

Other melodies with phrases that start above the break, then descend are introduced as well. For example, “Reuben and Rachel” or “Li'l Liza Jane” start on the second C, then descend to below the break, and are useful for students to practice as well.

________________

[1] These examples were chosen because they cross the break using the described intervals, they avoid other fingering challenges, and they are generally pretty familiar to most students. The entire piece may not work, so adapt with caution.

The other day I was enjoying a meal at a burger joint in town when I found myself distracted by the music playing. The song wasn’t familiar to me, but I recognized the chord progression as the same as “Desire” by U2. (Actually variations of this chord progression show up in lots of places, “What I Like About You,” “Cherry Cherry,” “Sweet Home Alabama,” and many others!) But here, it seemed somehow different. It took me a bit more listening, but I finally figured it out. Even though the chords seem to be the exact same as “Desire,” they were working differently. I used SoundHound to figure out the song was “Steal My Sunshine” by Len.

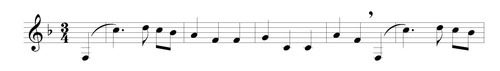

A, E, B would be the chords for both songs. [1] The last chord, B, would be home base (the tonic) in “Desire.” This is how this common progression normally works in popular music. But, in “Steal My Sunshine,” the second chord—E—is tonic. If the chords sound exactly the same, why would the tonality be different? Because the melody puts us in E.

You can see in the short excerpt of the melody and chords from the chorus above, that E is the most common note. Even when the chord changes to B and the E should clash, it serves as a tonal anchor of sorts.

In the Nashville number system, “Desire” would be flat 7, 4, 1.

“Steal My Sunshine” would be 4, 1, 5.

Have a listen and see if you can hear the next-to-last chord as home base in “Steal My Sunshine,” and the last chord of the progression as home base in “Desire."

[1] "Desire” is in a different key, but the relationship is exactly the same as “Steal…"—descending fourths. I’ve transposed it here so the chords are the same to make the comparison easier.

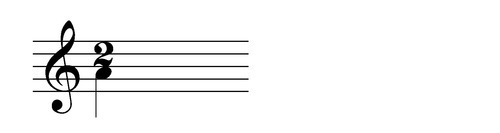

Fair enough. After telling them they are correct, I usually tell them my preference for thinking about time signatures. Something like this: "2/4 means there are two quarter notes in a measure.” Sometimes I even draw a sample Orff-type time signature to demonstrate.

So, If there are two ways of thinking about 2/4 (or anything/4), then why choose the latter? I have two reasons.

Think about the second movement (Adagio cantabile) from Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 8. It’s written in 2/4, but it’s adagio, and played so that the eighth note is perceived as the pulse. You simply can’t say that there are “two beats in a measure."

*Thinking about the number of notes—as opposed to beats—in a measure gives the student a framework for approaching compound meters like 6/8 (six eighth notes in a measure) or odd meters like 5/8 (five eighth notes in a measure). Learning only that there are x number of beats… does not equip students in the same way. There are so many beginners who, after being introduced to it, are consistently stumped by 6/8. By and large, my students who learn this way have success understanding compound meters.

I guess I have a third reason to throw in the mix. It is simply easier to say "there are two quarter notes in a measure” than “there are two beats in a measure, and the quarter note gets the beat.” Half the amount of words for a hopefully clearer picture.

—————

*This doesn’t mean that I don’t think learning about beats is important, or don’t teach it. I simply introduce time signatures to my students this way.

[This post originally appeared on my Posterous blog, which no longer exists. I’m posting it here so it doesn’t disappear from the internet.]

“[T]he evolution of no other art is so greatly encumbered by its teachers as is that of music.” Arnold Schoenberg (Theory of Harmony)

“It’s like solving a puzzle, rather than dealing with the overwhelming possibilities of infinite space (while crippled by the responsibility of free choice)."

Twelve Tones (by kindred spirit, Vihart)